mines, Cumbria

mines, Cumbriapage 69:- "MINING."

"Mines generally occur in hilly or mountainous districts because the presence of veins can be detected more readily where the solid rocks are either totally denuded or are very near the surface. No doubt rich metalliferous deposits occur in flat districts; but as the rocks are covered by a thick alluvial deposit, they are not so easily discovered."

"The mode of working mines differs in detail according to the situation and other circumstances which may influence it; but the general principle is much the same in all. If ore is discovered in an elevated situation, it is worked by a series of horizontal tunnels or levels driven along the vein, and the ground above and between the levels is afterwards "stoped" or "headed" out, or that part of it which contains sufficient ore to pay the cost of working. Should the ore continue downwards, below the lowest adit level, a shaft is sunk, in some cases upon the hade of the vein, and in others vertically by the side of it. In either case levels are driven off from it along the vein, in opposite directions, from ten to twenty fathoms apart, and the intervening spaces are afterwards headed out."

"In commencing "Heading," five or six feet of the vein is cut away above the roof of the level, for three or four fathoms in length, then strong timbers are fixed across, about three or four feet apart, where the roof of the level originally was; over these longitudinal timbers are placed, and above these a covering of fragments of rock or vein-stone. This structure is called a "Bunyan" or "Bunnin," and is made sufficiently strong to support the debris which accumulates upon it. As the miner cuts the ground away above, he retains sufficient of the debris beneath his feet to raise him up to his work, and throws the surplus down to the level below, whence it is carried out to the surface. In this way he proceeds until he reaches the level above, after which the whole of the debris upon the bunyan, or that portion of it which contains sufficient ore, is carried out to the dressing floors, where the ore is separated from the vein-stone and other earthy matter, and made fit for the market."

"The difficulties and dangers which beset the miner are of no ordinary kind. In some places the rock is so extremely hard that it can scarcely be penetrated by the finest tempered steel; in others it is so soft that considerable engineering skill is required to prevent it from falling down and rendering his past labour abortive. In some mines springs of water are cut, which almost defy the most powerful machinery he can bring to his aid, and his life is often endangered by falling rocks, impure air, and noxious gases; but by patient industry, and the skilful use of the appliances at his command, he overcomes all his difficulties."

page 70:- "The tools chiefly used in cutting rock are picks, hammers, and jumpers, or drills. Where the ground is moderately soft, the pick is mostly used; but where it is hard and tough, it is cut by blasting with gunpowder, or some higher explosive. Fifty or sixty years ago, when gunpowder was the only explosive used, this was done by boring a hole in the rock, from one to two feet in depth, as circumstances might require. When sufficiently deep, a charge of gunpowder was placed in the bottom of it, and an implement inserted called a "pricker," which consists of a slender rod having a loop at one end and gradually tapering to a point at the other end. The remainder of the hole was then firmly filled up with soft rock, and the pricker withdrawn, and a straw filled with fine powder inserted in its place. A slow match was then lighted and placed beneath the end of the straw, which allowed the miner sufficient time to retire before the explosion occurred. A preparation of nitro-glycerine, called dynamite, which possesses an explosive force nearly ten times greater than that of gunpowder, is now chiefly used in mining. Machinery has also been introduced for the purpose of supplementing hand labour in blasting. Rock drills, driven by compressed air, are supplied by several firms, and by their aid levels can be driven and shafts sunk at three times the speed of hand labour, and at considerably less cost."

"Before the invention of gunpowder, levels were cut through hard rock by the miners of those days with "stope and feather," implements consisting of two thin pieces of iron, called feathers, about six inches long and half-an-inch broad, flat on one side and round on the other, and a thin tapering wedge or stope of the same length and width. A hole was bored in the rock and the feathers placed in it, with their flat sides together, and parallel with the cleavage of the rock; the point of the stope was then introduced between them, and driven in with a hammer until the rock was rent. This must have been a very slow and laborious process, because those who made use of it were very careful not to make the aperture larger than was required to admit one man. There are still remains of these primitive works in several of the mines in the Lake Country; levels measuring from five to six feet in height, and eighteen or twenty inches in width, and which only require a very superficial inspection to convince any one that the old miners must have been very expert in the use of these tools."

"Occasionally the miner's progress is stopped by an immense quantity of friable quartz, deposited so loosely that it will not support itself, but falls down as rapidly as he removes it in attempting to make a passage through. To overcome this difficulty he constructs a number of strong oblong frames of timber, of the same dimensions as an ordinary level. Having erected one of"

page 71:- "these frames, he takes a number of straight poles, two or three inches in diameter and six or eight feet long, sharpened at one end, and drives them forward with a heavy hammer into the loose quartz, on each side and along the top of it, and sufficiently close to each other to prevent the quartz from running through. And while these support the loose quartz, he removes a part of it from the space which they enclose, and erects another frame a few feet in advance of the last, and then proceeds to drive other poles forward as before."

"An open vein like the one just described becomes a huge conduit, collecting water from the surface and from every crevice in the rock, and a shaft sunk upon it can only be drained by the aid of powerful machinery. The pumps used for this purpose are an enlargement of those employed in supplying elevated cisterns, and in raising water from wells, and are so well known as to render unnecessary any description of the principle upon which they are constructed."

"The development of steam power and improved machinery for pumping has been the means of opening up many valuable mineral and metalliferous deposits, which, with the limited power and imperfect machinery possessed by our forefathers were altogether inaccessible; and the modern system of loading wagons in remote parts of the mine, conveying them along tramways into an iron cage in the shaft in which they are drawn up to the surface and thence along other tramways to the dressing floors where their contents are discharged, is as great an improvement upon the wheelbarrows, jackrowls, and kibbles of the past, as the beautifully bored iron working-barrels and their pistons fitted with steel springs, are upon the wooden pumps of bygone days."

"When the miner has penetrated into the earth a distance of fifteen or twenty fathoms, either vertically or horizontally, the supply of fresh air fails; his candle refuses to burn unless it is placed in a leaning or nearly horizontal position, and he experiences difficulty in breathing, therefore it becomes necessary to create a current of air by artificial means. In some cases this is done by machinery, and in others by means of a waterfall, and the current thus created is conveyed to the workmen through wooden tubes; but the most natural and easy means of ventilation is to have, where practicable, more than one opening into the mine, by which a free circulation of air will be produced spontaneously."

"Noxious gases are frequently liberated from cavities in the rock, which have a very injurious effect upon the miner's respiratory organs; and these, combined with the mineral dust which he inhales, produce in him the seeds of disease and premature old age. He becomes an old man at forty-five or fifty, and rarely lives out the allotted term of three score years and ten. But I cannot think that the beneficent God who called into being the agents"

page 72:- "by which fissures were formed in the earth's crust, and afterwards stored with mineral wealth, intended that the men who opened those store-houses of nature, should have to surrender one-fifth of the ordinary term of life. Sir Humphrey Davy and others, to whom all honour is due, have by their invention of safety lamps, prevented much sacrifice of life, and rendered practicable the working of many coal mines, which, otherwise, must have remained for ever closed; and cannot some of our scientific men invent a guard for the miner's lungs, or some means of neutralizing the baneful effects of mineral dust and foul air? This subject is worthy the attention of our medical men."

"The miner's labour does not end when the ore he has obtained is brought out to the surface; a great deal has yet to be done on order to make it fit for the market, as it is generally largely mixed with vein-stone and other earthy matter. The first process in dressing is to draw the stuff over a grate, upon which a stream of water falls; the smaller part of it passes through the grate into a tank below, and the remainder, cleansed from the mud with which it is covered, is passed onto a table where it is picked by hand. The stone is separated from it, and the pieces of pure ore carried to the ore-house; but a considerable quantity remains. consisting of a mixture of ore and vein-stone or quartz, which must pass through a crushing mill before they can be separated. The ore and vein-stone thus crushed, and that which passes through the grate before described, were in early times separated by a process called "Tubbing." In this process a large tank or tub filled with water was used; above it were suspended one or more shallow oblong boxes, called "sieves," having wire network bottoms. After a quantity of the crushed ore and stone had been placed in one of the sieves, it was lowered into the water and agitated for a few minutes, either by hand or by machinery; this caused the ore, which has the greater specific gravity, to sink to the bottom, leaving the stone on the top. It was then again raised above the surface of the water, when the refuse was taken off and thrown away, and the ore removed; the sieve could then be refilled and the process repeated. In modern methods the sieves are fixed and the water is caused to pulsate through them by wooden floats, to which a gentle vertical motion is given by machinery. These machines deal with the ore and vein-stone in various sizes into which it has previously been separated, ranging from fragments nearly as large as hazel nuts down to fine sand, separate machines dealing with each size. Finer sand containing ore is separated by machinery and processes of various kinds, nearly all of which depend upon the greater specific gravity of the ore."

"The water used in all these operations is made to pass through large pits, where all the muddy sediment contained in it is collected, and a considerable quantity of ore obtained therefrom."

page 73:- "All that now remains to be done is to transform the ore into metal by smelting. This is done by placing it in a furnace, together with certain substances, which by their chemical action, assist the fire in reducing the ore to a fluid state. When this takes place, the molten metal can be freed from the slag and allowed to flow out of the furnace. It has still to undergo a refining process before it is fit for use, and if it contains silver, that precious metal has to be extracted from it."

"A Mine Agent or Manager, in order to be fully qualified for his office, should possess an extensive fund of both theoretical and practical knowledge. He ought to be acquainted with Geology and Mineralogy; be familiar with ever detail in mining, and able to adapt it to every locality; have a knowledge of all kinds of water, steam and electrical engines, drawing, pumping, dressing, and other mining machinery; and be able to test ores, by assaying, when required. It is also important that he should be acquainted with the arts of dialling and drawing plans, by which he can have all the internal works of the mine accurately delineated on paper, and by this means be enabled to arrange and adopt the most efficient method of conducting future operations. And thus man's mental, as well as his physical powers, are called into vigorous action, in searching out and obtaining possession of the mineral treasures of the earth, which an all-wise and beneficent Creator has provided for his use."

page 74:- "THE MINES OF THE LAKE DISTRICT."

"Mining, as a branch of industry in the Lake District, dates back to a very early period, indeed it is highly probably that the aborigines who dwelt here when implements and weapons of bronze began to take the place of those formed of stone, were the first to search for and dig up the ores that increasing knowledge had taught them to use. It is true that we have no tin in the Lake District, but the proportion of that metal used in the alloy (about 8 per cent.) was so small that the quantity required would be easily conveyed to a locality where copper was plentiful. Britain was noted for its mineral wealth long before the Romans took possession of it, and those energetic pioneers of civilization knew how to make use of the treasures they acquired by conquest. "Britain produces gold, silver, and other metals, the booty of victory," was the language used by Agricola, for the encouragement of his soldiers when he led them to attack the Caledonians under Galgacus, and the cohorts that were stationed at Galava (Keswick),*to guard the fords of the Derwent and the Greta, and the legions, with their camp followers, who passed and repassed through the valleys and over the mountain passes, to and from their stations on the great wall, could not fail to discover the presence of copper, lead, and zinc, while constructing their roads and fortifications. They left no written records to show how far they engaged in pursuits of that kind, but many of our old mines give evidence of work done in very early times, some of which was no doubt done by the Romans. There is good reason to believe that mining has been actively carried on in this district for about two thousand years, and much of the history of the Lake Country is associated with its mines."

"In Gibson's Camden's Britannia, we are informed that Keswick is "A little market town, long since noted for its mines (as appears from a certain charter of Edward IV.), and at present inhabited by miners," (A.D. 1607). And in speaking of Derwentwater, he says, "It contains three islands, one the seat of the Ratcliffe family, the second supposed to be that on which St. Herbert lived a hermit's life, and a third§inhabited by German miners.""

"In 1561 a Company was incorporated for the purpose of working Goldscope and Dale Head Mines, where copper ore was found in great abundance. This was very probably the first Mining Company formed in the North of England, and undoubtedly the most aristocratic, as it was patronised by aldermen, noblemen, high officers of state, and even royalty itself. Extensive copper smelting works were erected in Keswick by this Company in 1565 and 1566, the largest in England, and probably in Europe at that."

"*See Paper by Mr. J. J. Bailey, entitled "The Maryport Camp - what was its name"? Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Association, Vol.12."

"§This is now occupied as the residence of John Marshall, Esq."

page 138:- "MINES IN THE IGNEOUS ROCKS OF THE LAKE DISTRICT."

"In the Eskdale Granite there are a great number of veins of haematite iron, some of which have yielded a good deal of ore, and the grass-covered mounds in Red Gill, on the southern side of Eskdale Valley, prove that some of them were worked in early times."

page 139:- "MINES IN THE CARBONIFEROUS SERIES."

"Some of the mines in the Carboniferous Rocks, although quite on the outer margin of the Lake District, are closely associated with it, and owing to their great importance commercially, ought not to be passed unnoticed. The veins in this formation are well mineralised, and numerous, in some localities, but they differ in one important feature from those in the older rocks, namely, the flats and irregular deposits connected with them. These flats or irregular deposits are of immense value, indeed, they have been more productive, both in Westmorland and Cumberland than the veins with which they are connected."

"LEAD MINES"

"On the western side of the Pennine Chain there is an important group of mines, consisting of Dufton Fell, Hilton and Murton, Knockergill Head, Silver Band, Amber Hill, Lowfield Hush, and Dow Scar Mines, also others of minor importance; some of them have been wrought very extensively, and have yielded large quantities of galena. This ore has been obtained chiefly from the Tyne Bottom and Jew Limestones, but the Silver Band vein contained ore in nearly all the strata, from the Firestone to the bottom of the Great Limestone. The veins in these mines differ in one feature from those of the Alston district, namely, with regard to the minerals that are associated with the galena. In the latter, it is associated with fluor spar, and in the former with sulphate of barytes; even in the case where a vein can be traced through the range of mountains, this difference is found to prevail on the eastern and western sides of the range. The general bearing of the veins is east and west, and their hade is toward the south."

"Some of these mines were worked at a very early period, probably by the Romans, or even before their advent. Ore has often been found in considerable quantities on the surface and in the alluvial soil where veins crop out to the surface, in the ore bearing strata, or "sills," as they are called, locally, therefore, its presence would be detected without an effort on the part of the early workers."

"The mines in this district are almost wholly wrought by adit levels, some of which have been driven a great distance, and where the rock is not sound, the roof has been arched with stone and mortar, instead of the usual bunyan constructed of timber. ..."

page 140:- "THE IRON MINES OF WEST CUMBERLAND."

"The deposits of haematite iron ore in West Cumberland cover an area of about eight or ten square miles, comprising a narrow strip on the outcrop of the carboniferous limestone, measuring about eight miles in length, from north-east to south-west, and from a mile to a mile and a half in width. The limestone reposes upon Skiddaw Slate on the south-eastern side, and is overlaid by coal measures on the north-west, except at the southern end, where it is covered by the St. Bees sandstone."

"The distribution of the ore deposits is irregular, and as there is rarely any indication of their presence on the surface, it can only be ascertained by boring, but they are so numerous that most of the ore-producing area is thickly studded with mines. They"

page 141:- "differ very greatly in shape, as well as in extent, and some of them are at a considerable depth below the surface. The prevailing form of the deposits is more or less flat, and they vary in thickness from a few feet to 40 fathoms, or upwards, but the thickness sometimes increases or decreases very suddenly, and there is the same want of regularity with regard to their lateral dimensions. A more or less straight and nearly vertical wall on one side of the deposits affords conclusive evidence that are in most, if not all cases, connected with a mineral vein. A few deposits have been found so near the surface that they could be worked as open quarries, and these open excavations have thrown great light upon the internal structure of the deposits. In one of these at Todholes, near Cleator, there was a superficial covering of from fifteen to twenty feet, which contained, in the lower part, numerous angular blocks of limestone; the floor of the deposit coincided with the dip of the limestone, and was formed of a white and red mottled shale, of the nature of fire-clay, and from thirty to forty feet in thickness: the upper surface of the shale was uneven, being thrown up into ridges, with corresponding depressions. Between the shale and the superincumbent haematite there was generally a band of conglomerate, from three to eight inches thick, composed chiefly of small pebbles of white quartz; above this was a magnificent bed of haematite, varying from fifteen to upwards of thirty feet in thickness, and sub-divided by irregular, but nearly vertical joints. Interstratified with the haematite, and parallel with the floor of the deposit, were two, and sometimes three, bands of shale, from one to eight inches thick, and of a greenish black colour; these, with the roof and floor dipping at the same angle as the limestone, gave to it much of the appearance of a true bed."

page 146:- "The earliest record respecting iron mining in West Cumberland refers to the gift of an iron mine at Egremont to the Abbey of Holme Cultram, by William, third Earl of Albemarle, who died in 1179, and about fifty years later, iron mining is mentioned in some of the historical records relating to Furness Abbey. It is more than probable, however, that some of the very shallow deposits in both Cleator and Furness districts were wrought at a much earlier date; an ancient working was broken into at Stainton Mine, in Furness, a few years ago, and two polished stone celts were found in it, lying in front of a body of ore, which their owners had probably been engaged in hewing. It is also probable that the Romans, who for many years held the important camp at Maryport, would detect the presence of iron ore in the Cleator and Egremont district, which must have been well known to them."

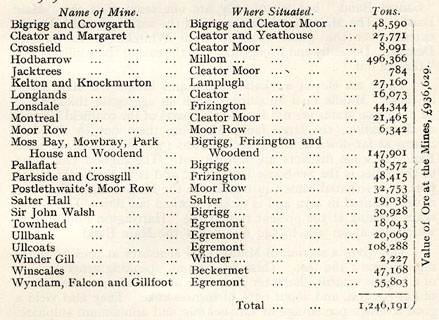

page 147:- "The iron mining industry, being largely dependent upon the state of the iron trade, has had many ups and downs; in 1860, the output of the Cumberland Mines was 466,851 tons; in 1871, it was 976,847 tons, and in 1887, 1,479,516 tons, being little over three times the quantity raised in 1860. In 1909 the produce of the Cumberland Mines was 1,246,191 tons (value L936,629) or 233,325 tons less than the produce of 1887."

"The following is a list of the Mines from which ore was raised in 1909:-"

click to enlarge

click to enlargePST3Tab5.jpg

page 148:- "THE COLLIERIES OF CUMBERLAND."

"The coalfield of West Cumberland, as described by Mr. Lloyd Wilson, has generally a west and north-westerly direction of dip, passing down under the sea along the coast from Maryport to Whitehaven. How far it extends in this direction has not yet been ascertained."

"The strata is disturbed by many dislocations, so that in one area a seam of coal may be just below the surface, and in another it may be found 1,000 feet below it. There are faults with "throws" up to 750 feet running in a northerly and southerly direction; in most cases, though, there are many cross faults also."

"The coal seams vary individually to a great extent in different localities, sometimes within short distances. A good example of this is the "Main Band," which is found at the north end of the district to be 5ft. 6in. thick, and at Whitehaven 12 ft. In most areas between these points it is found in two separate seams with varying distances between them from 18 inches to 30 feet."

"The top portion is called "Metal Band, and the bottom "Cannel Band," but where they are one seam it is the "Main Band." The Main Band, and most of the seams of coal below it, extend over the whole coalfield from Whitehaven to Bullgill, Dearham, Dovenby, and Broughton. To the east of these villages it is "thrown out.""

"There are eleven workable coal seams besides the Main Band in these "Middle Coal Measures," with an aggregate thickness of 32.2. These seams are not found in all parts of the coalfield because of denudation, the large faults throwing them out to the day. Seams as far down as the Three-quarters (360 feet below the Main Band) in some districts are thrown out. The highest coal seam of the series is the Senhouse High Band and is worked near Maryport, it is situated some 640 feet above the Main Band. This coal is very limited in area and is mostly worked out now. The lowest seam working at the present time is the "Harrington Four Foot," which lies about 484 to 540 feet below the Main Band."

"This gives a section of Middle Coal Measures at present working of some 1,180 feet. These coal seams, speaking generally, are of a highly volatile character and yield about 10/11,000 cubic feet of gas per ton, and about 65% of furness (sic) coke. They also yield a good average percentage of tar, benzole and ammonium sulphate. The Main Band seam is looked upon by geologists as the most interesting, because it is found to contain a splendid series of fossil flora, some of which prove this coalfield to be of "Middle Coal Measure Age." These examples of beautiful vegetable life are embedded in the roof shales just above the coal. There are examples of large sigillaria, 20ft. long, lying in the same shale beds as the most delicate "Sphenopteris furcata," "Sphenopteris"

page 149:-

click to enlarge

click to enlargePST341.jpg

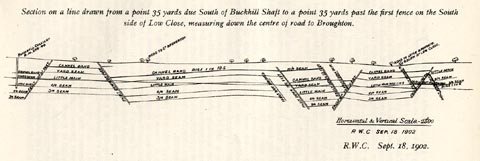

"Geological section, Buckhill Shaft to Low Close, by RWC, 1902, Buckhill Colliery etc, Great Broughton, Cumberland, published by W H Moss and Sons, 13 Lowther Street, Whitehaven, Cumberland, 1877 edn 1913."

"Section on a line drawn from a point 35 yards due South of Buckhill Shaft to a point 35 yards past the first fence on the South / side of Low Close, measuring down the centre of road to Broughton."

"Horizontal & Vertical Scale - 1/2500 / R.W.C SEP. 18 1902"

page 150:- "The occurrence of a good fireclay on the high ground between the sea and the River Derwent is of importance to this District. The clay has been heated up to 3,000°Fahr. and is equal to the best Staffordshire clay so long unrivalled. This mineral is used in lining blast furnaces and stoves, also in building bye-product coke ovens, all of which work up to a very high temperature. This material would have to be brought from Staffordshire or Newcastle Districts if it had not been found here."

"This clay is full of fossils such as calamites and sigillaria and lepidodendron, specially the rootlets of these plants. There is usually a seam of inferior coal lying on this fireclay, and the fireclay lies upon a bed of ganister with a high percentage of silica in its composition, but this does not persist over the whole area of the clay formation."

"The use of coal was partially known at a very early period, indeed there is reason for supposing that the British aborigines were not ignorant of its use, their hammer heads, wedges and stone and flint axes having been found associated with it; and a people who are known to have wrought veins of lead, tin and copper, could hardly have remained ignorant of a useful mineral and fuel that lies equally near the surface. Moreover, fragments would be continually washed out of their native beds, borne into the plains by floods, and their suitability for fuel made known by accident."

"The Romans who occupied our island were undoubtedly acquainted with the use of coal, as unburnt fragments and cinders have been found in Roman walls and roads, and Roman coins in beds of cinders and ashes. It is mentioned by St. Augustine and other ancient writers, about the beginning of the seventh century; and there is other historical evidence of its having been used by the Saxons in the seventh century. It is also said that there is an"

page 151:- "ancient document extant which records the gift of certain lands to work coal, to the monks of Dunfermline, about the twelfth century"

page 154:- "The entire produce of the coal mines in Cumberland in 1815 was about 200,000 wagon loads, or 450,000 tons. In 1859 it amounted to 1,041,890 tons; in 1873, 1,747,064 tons; in 1888, 1,796,594 tons; and in 1909, 2,309,370 tons, being an increase over 1815 of 1,859,370 tons."

page 155:-

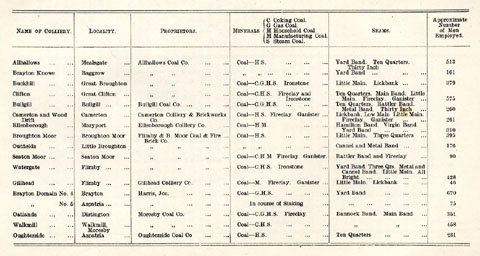

click to enlarge

click to enlargePST3Tab2.jpg

page 156:-

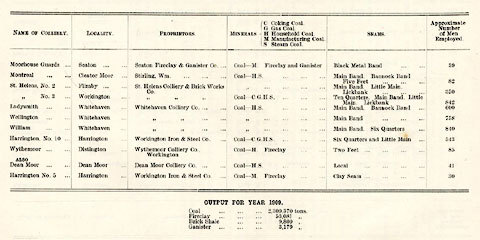

click to enlarge

click to enlargePST3Tab1.jpg